Building Bigger Biceps: Live Training Q&A Transcript

The transcript of my live Facebook session breaking down the science of biceps training and how you can add serious size to yours.

The transcript of my live Facebook session breaking down the science of biceps training and how you can add serious size to yours.

Note: This tutorial video was recorded as a live Facebook event. The text below is an edited transcript of the tutorial intended to provide members with a convenient means of referring to and further researching the topics and content detailed in the video.

Hey guys, Dr. Jim Stoppani, and today I'm going to be talking about how to build bigger biceps. I'm coming to you live from my new JYM in Hollywood. Now, you probably notice there's still not a lot of equipment in here. I'm still waiting on much of it to come in, but I've got the Sorinex cage, I've got a few Rogue pieces of equipment like the glute/ham raise, reverse hamstring extension—which you guys know I'm a huge proponent of doing that exercise and building up the posterior chain—and then we've got the dumbbells. So, that's pretty much all I have to teach you guys how to build bigger biceps, but really that's all we need.

So, I'll be doing these tutorials more frequently. The JYM Army has been watching me do tutorials almost every Sunday. I go through my Train with Jim series . On the Bodybuilding.com platform, I'll also be doing more of these live tutorials where I'm teaching you guys different topics like today, which is building bigger biceps.

Today, I'm going to cover a few topics. We'll start with anatomy, which is very critical for understanding how to train the biceps. Once we've covered anatomy we can get into biomechanics, how different arm positions change the muscles that are being used. Then we'll talk about program design: How do you, then, knowing the anatomy, knowing those biomechanics—the different moves that you need to do—how do you create the best program?

We'll also talk about the involvement of genetics when we talk about length of biceps and the peak of the biceps, and then I'll cover some novel tricks for building up the biceps that you probably haven't tried like open grip, offsetting your grip on the dumbbell so that you have more weight on one side while you're doing supination, seated barbell curls, things like that.

We'll go through all of these, but today I'll be taking five questions—I have my team going through—so post your questions that you have about biceps training now. We're going to pick five of the best questions today. I will answer those questions, and if your question was chosen you will receive a JYM System. That's my Pre JYM, my Post JYM, and my Pro JYM —flavors of your choice. So get your questions in on biceps training.

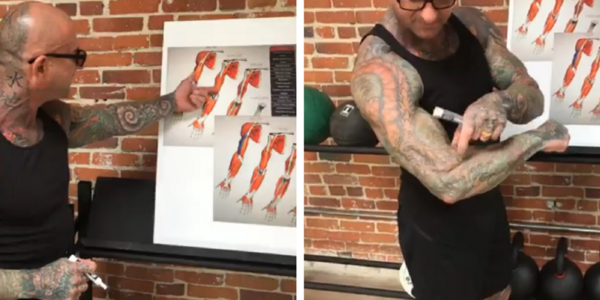

Let's go to anatomy, now. We're going to go over here to the diagram. Unfortunately, with these live sessions, I can't get too digitally advanced with showing you guys anatomy, so we're going to have to stick here with the posters, and then I'll get some models as well to make it a bit easier for you guys to see.

Anytime we're talking about the biceps—the word "bi" is in there, right? Bi-ceps. That means "two", and it has to do with the two separate heads on the biceps which we can see right here. Here's our long head, it's going underneath the deltoid here. The is the right arm. This is the outer head or what's known as the long head of the biceps, and you can see where it's separate right here, the different tendons that come up here.

Now, the short head—over here—is that inner head. It's called the "short head" because it actually attaches to the top of the upper arm bone, the humerus. The outer head is called the "long head" because it actually attaches further up. It crosses the shoulder joint where it actually attaches to the scapula.

Because the long head attaches to the scapula, and because the short head attaches to the humerus—the upper arm bone—when you bring your arm behind you it doesn't change the length of the short head at all, but it changes the length of the long head. That's why doing behind-the-back or incline curls, where the arms go behind the back, tend to hit more of that long head of the biceps. We'll talk about how that's critical for the peak.

When we talk about biceps, we're talking about these two superficial muscles. They come down and converge on the same tendon here on the forearm, and the main motion is flexion of the arm at the elbow.

Now, the other thing that the biceps do is they supinate as well, so they turn—you see the biceps moving when I'm turning my palm up? That's supination. The biceps are going to help curl the arm, but also supinate, which is why we do some supination moves when we do curls. And we'll talk about that. But that's the biceps.

In addition to the biceps, there are two other muscles that you want to be concerned with: The brachialis, which we can see here—if we remove the biceps, which are on top of the brachialis—lying deep underneath the biceps. So your biceps, here's the long head—my biceps long head literally ends right there, I'll draw right on it. You can literally see where my finger goes into the muscle. That's going behind the long head of the biceps, and here is the brachialis.

We can see it here, it's just attaching to this humerus—the upper arm bone—about the midway point, you see the short head is going up higher so the leverage is different, right? When we're talking about the length of this lever arm and where it's contracting from, you can see with this shorter muscle this is why the brachialis helps to initiate the curl. We're going to talk about these muscles and where they're involved during the range of motion.

It's that brachialis that I'm always talking about, that deep underlying muscle. While you can't really see it well, it's important to build up the brachialis because the bigger this is the more it's going to push the biceps out, give you bigger arms. As well, when you're really defined—and it's hard to see with all the ink on me—you can actually see the separation between where the triceps lateral head ends, where the biceps long head ends, and where the brachialis is.

On a very lean bodybuilder, you can actually see that muscle. Most of us, we can't see, but for a very lean bodybuilder, you can. You want to build that up if you're lean, but also to help build up the biceps. That's going to help increase overall strength on curls. The more weight you can lift in relation to what you did previously, the bigger you can build muscle.

Now, the other muscle we want to look at is this forearm muscle right here. This is called the brachioradialis. The brachioradialis is a forearm muscle that actually crosses the elbow joint. It's one of the few that crosses the elbow joint, and because it crosses—it's that muscle that you see right there on the outer part of the forearm, right there on the outside of the elbow. It's that, right there. Because it crosses the elbow joint the brachioradialis also helps when we curl our arms.

So, those are the four muscles that we're concerned with, and I'm going to talk about where they're involved during that range of motion when we're talking about training the biceps. Brachioradialis assists the biceps, as does the brachialis. Then, we want to be concerned about where these muscles originate from—like I said, the long head is up here on the scapula so it's crossing the shoulder joint, whereas the short head attaches to the upper arm bone. It's going to change the muscle involvement when we move our arm to do different types of curls.

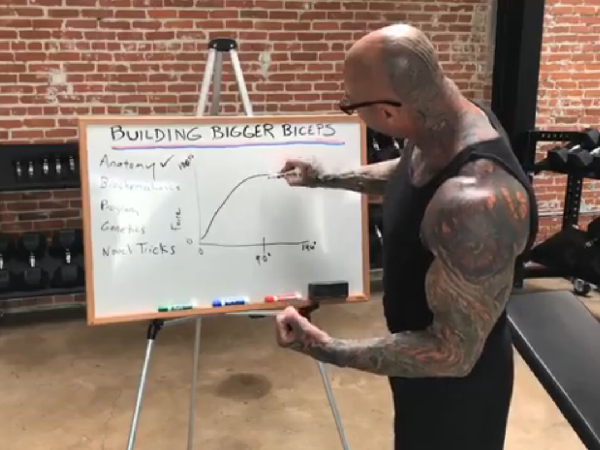

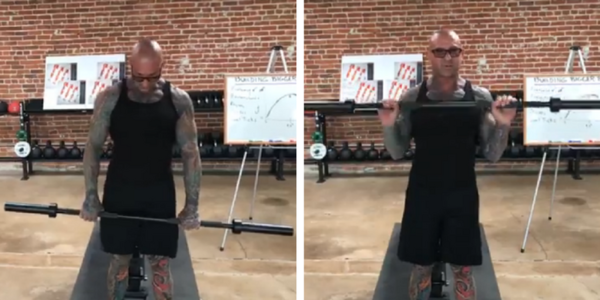

So that's our basic anatomy. Now, I want to get into the biomechanics, so let's go back over to the whiteboard here. With any exercise—whether it's an angular move like the biceps curl, because we have one joint moving and you can see that it moves in an arc, it's not like the bench press which is moving straight. It's angular. Regardless of whether it's the bench press, whether it's the curl, whether it's a row, we have what's known as a "strength curve".

The strength curve—if this was zero for force production, how much force that the muscle could produce, and this is 100%—and then this is the range of motion, so here I've got straight arm over here, so this is the amount of flexion that's going on—with a straight arm that's zero—and up to here we can get close to—all the way up would be 180 degrees, right? We can't get quite to 180 degrees, so we'll say somewhere around maybe let's say 140 degrees. So that's the top, then. This is the arm straight, this is the arm at the top; this is no force, this is max force.

When you do a curl, the very beginning you're at the weakest point. Then, you get stronger, stronger, stronger—right up to about the 90-degree point, where the arm is bent halfway. That's right where you're strongest. Then, once you pass that point, your force production goes down, so it's sort of bell-shaped if you will, or at least a curve shape. It's not really, truly a bell here because it starts and comes right up.

So, what does this mean when we're doing the curl? It means you're weakest at the start position, you're strongest at the halfway position, and this has to do with the biomechanics—the anatomy that we talked about: The brachioradialis and the brachialis. Because they attach lower on the upper arm bone, they're better at initiating the movement because it's a shorter lever arm. So they help to initiate the movement, but they're very weak, so this part of the range of motion is quite weak.

When you get to the halfway point, the biceps start kicking in. This is where the biceps really work, and this is why I recommend doing things like seated barbell curls, because we're removing the weaker brachioradialis and brachialis from the picture so that now we're just curling for that strongest range of motion.

Why is that important? Well, let's say you could only really move 100 lbs in this direction because you're weaker, but you could move 200 lbs in this direction. If you could only move 100 lbs in this direction and you're going to curl through the full range of motion, but you can curl 200 lbs in this direction—but not here, when you're starting here—you're never going to get 200 lbs to this point because your arm is weaker in this position.

So, you're literally limiting yourself if you do a full range of motion curl every time to how strong you are in this range of motion, and in fact isn't that where we hit failure? Right down here—isn't that why we cheat? This is why you cheat. You throw it up to get the weight moving, it passes the weak range of motion and then those biceps are kicked in, and now we can move the heavier weight. That's why we cheat that way, it's because we're weaker in this range of motion.

By doing exercises like—and I'm not saying you should do this all the time—and I'll talk about this when we get down to the novel tricks—doing an exercise like the seated barbell curl where you're not bringing the arm all the way down means you're not limiting your strength to this part of the range of motion.

You're limiting to here where you're strongest, so it helps you to place more overload and it prevents you from fatiguing on curls when the brachioradialis and brachialis have fatigued but the biceps still have far more energy and strength to keep going. That's all due to the strength curve, and the strength curve is due to the muscles that get involved during those ranges of motion. That gets back to where those muscles attach on the arm.

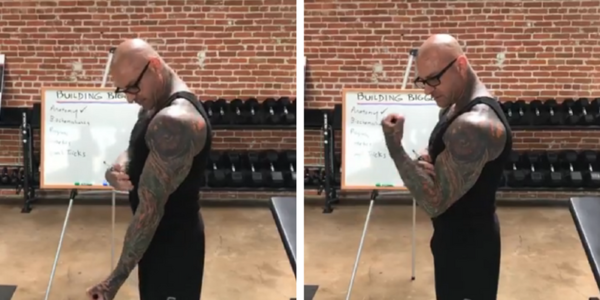

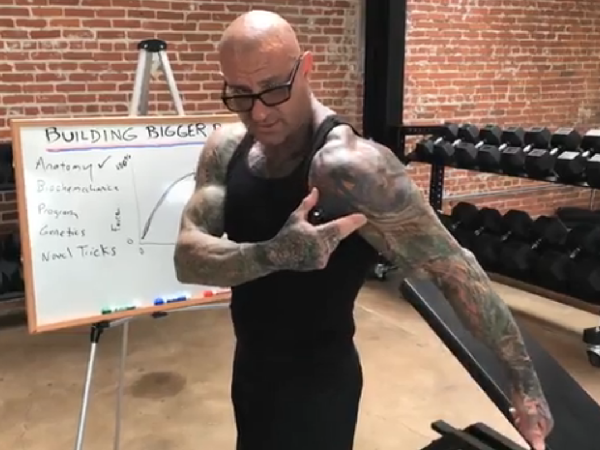

The other thing that I want to talk about with the biomechanics is arm position and the biceps heads. Now, as I talk about the two different heads—we have that long head, the outer head, and then we have the shorter head which is the inner head—on me you can see where the short head ends here on this border, and where it connects, where it comes right up against that long head, right? So this attaches right here, whereas the long head keeps going up and attaching higher across the shoulder.

Now, because of that—because of where the long head attaches—when I bring my arm back it stretches the long head. But like I said the short head attaches to the humerus, the arm bone, so it's not changing its length no matter where I move my arm. It's just changing the length of the long head, making it stretch longer the further back I go.

What does a muscle do when you stretch it? It can contract with more force than if you just contract it before stretching it. Stretching that muscle to its full length can actually help you produce more force from that muscle. So any time the arms move behind the body like an incline curl—see, if I were standing upright now, my arms would be here and this would be my range of motion, but since I'm seated at an incline it allows the arms to go behind my back, meaning I'm stretching that long head.

Because I'm stretching the long head and that long head can now apply the most force it becomes the strongest mover when I do my curls, which means it will take the majority of the force when I'm lifting over the short head, because the short head is not being stretched. So, when you stretch that long head, like I said, it allows it to contract with more force and then it can be the dominant mover when you're doing curls.

Another way to do this, not seated but with either cables—I don't have any cables in here, yet, but with the bands is the behind the back curl. With a low cable or a band, I can now—you'll typically see people want to curl this way, right? Which is fine, but if you stand with the line of pull coming behind the body, now the arm goes behind me, and now when I do curls as long as I'm keeping that elbow back behind me and not trying to cheat and do this—keep that arm back—I'm using more of that long head.

When we talk about the biceps peak, few people realize that even though the biceps peak—even though the long head is on the outer part of the biceps, that when we make our muscle we do it this way and not this way—if you look at my anatomy here you can see, here's the short head—watch when I make my biceps flex, this is short head right here, so where's the peak coming from? This is all long head over here. That peak is really coming from the long head.

So if you really want to maximize the size of your peak—and again, your peak is somewhat genetically predetermined, doesn't mean you can't get it better; this is the way to get it better, focusing on exercises that target more of the long head, and one of the ways we do that is by doing exercises where the arms come behind the body.

Now, another way to target that long head without putting your arms behind your body is to rotate the arm. With the concentration curl—whether you're doing it standing or seated; I'll just do it seated, I know most of you are familiar with my standing technique—but regardless, when you do a concentration curl look at the position of my hand in relationship to my elbow. When I'm doing curls normally, I'm curling in front of the body. Here, I'm curling pretty much sideways, right?

What's happening when I go from curling in this direction to curling in this direction? I'm still flexing the arm, right? Nothing should change, right? Wrong. This is what's great about the human body—biomechanics. When you medially rotate the arm—which means simply turning it in—due to the biomechanics involved and the way that the biceps are lined up when you're doing the curl, it puts the long head as the stronger mover.

So again, even without stretching it, just by medially rotating the arm, it places that long head in a position that allows it to supply the most force over the short head, and this is why concentration curls are so popular and so effective for building up biceps peaks. It's that medial rotation, it's the way my arm is rotated in.

To hit the long head, you have two techniques that I've taught you so far: Bringing the arm behind the body and keeping the elbow behind the body while you curl; medial rotating the arm in; and there's one more that you're probably not familiar with, and that's the neutral grip.

Believe it or not, doing curls with a neutral grip—or what's called "hammer curls"—actually places more focus on the long head. Turning the wrist places that long head as the stronger mover during this curl, meaning the long head is taking on the majority of the force. Being the prime mover, it's taking much of the force.

Now, another way you can do this is with an EZ curl bar. I want to show you the difference here. Even though it's not a true neutral grip you'll notice that with a standard barbell my hands are pretty much supinated, straight up and down, right? My palms are straight up toward the ceiling. Neutral grip, my palms are facing each other. With an EZ bar, it pretty much puts you halfway between a neutral grip or hammer grip and the standard underhand grip.

Here, you're getting a slight what's called "pronation". Remember, the biceps help to supinate the arm—that's supination—but this motion, turning the wrist in is called pronation. So, holding—even though the biceps help to supinate, so when you're doing your curls you can supinate curls to hit more of the biceps—however, the other way to focus more on particularly that long head is to stick with that pronated grip, a more neutral grip, or try the EZ bar which puts you at a slight pronation to help target more of that long head.

Now, the other way to actually medially rotate the arms in—remember, we've got three techniques now for hitting the long head: Bringing the arms behind the body, using a neutral grip, and medially rotating the arm which I should you with a dumbbell. You can also medially rotate your arms more on a barbell. How do you do that? With grip width.

The wider I go on a bar, the more my arms are turned out. The closer I grab the bar, the more it turns my arms in. So you can try a close grip on the barbell to get some medial rotation on the arms while you're doing your curls and that's going to hit more of the long head.

The opposite pretty much holds true for targeting the short head. Now, I've talked a lot about that biceps peaks and with it being mostly from the long head, but that doesn't mean you want to neglect your short head. Remember, the short head is what's going to give the biceps thickness, especially on the inner part of the arm. So you don't want to have an underdeveloped short head or inner head on the biceps, so you definitely want to be also working your short head as well.

The way you do that is—well, let's talk about the opposite motion of what we talked about with the long head. So with the short head, medial rotation is not going to work, right? it's going to be the opposite. So we're going to laterally rotate or turn the arms out. A wider grip on a barbell is going to help you hit more of that shorter head, the inner head.

What you use a typical shoulder-width grip, you're pretty much even—both long head and short head are pretty much providing an even balance. It's actually a little more on the short head in this position. The wider we go, the more of that short head involvement I'm going to get.

Just as I showed with the dumbbells, you can turn your arms in to do concentration curls and hit more of the long head, you could do your dumbbell curls with the arms turned out—you could do this on an incline as well—but here even though you're on an incline which brings the arms back, if you turn your arms out and do your curls it's going to focus more on that short, inner head because of the position that my arms are in: Laterally rotated, they're externally rotated out, and so I'm hitting more short head.

For short head, wider grip on the barbell, turn the hands out on dumbbell curls, and the other thing is bringing the arms in front of the body. Now, remember, I said bringing the arms behind the body stretches the long head, so what does bringing the arms in front of the body do? It doesn't stretch the short head, it places the most slack on the long head. With a lot of slack on that long head, it's no longer stretched—it's not supplying a lot of force. Now the medial head can take over. This is why preacher curls are good at working the inner head.

Also, what's known as the high cable curl—I'll have to demonstrate on bands for you guys—but in the high cable curl—you'll normally do this in a cable crossover station, you'll grab one cable and then you could either do this with two arms or one. So what are the biomechanics here?

Well, I'm bringing the arm up and not stretching it, right? It's going to be up and turned out, so now we're doing both. We're putting slack on the long head by bringing the arm up versus back, and we're turning the arm out, so we've got both that external rotation and bringing the arm forward even though it's out to my side. This really is a great exercise for hitting that short head of the biceps because of the arm position.

So those are the main ways to go about hitting those two different heads. As far as the brachialis—when I talk about neutral grip curls, a lot of people think that the hammer curl's great for the brachialis, and it is. It hits the brachialis, but it also hits the long head. Because the long head is a much stronger mover than the brachialis it's really that long head bicep that sort of takes over on hammer curls.

A better option is to go and simply do reverse curls—an overhand grip on the bar, that's your best bet for actually working the brachialis. Why is that? Well, it's also working that brachioradialis on top of the forearm, as does the hammer curl a bit, but because the biceps aren't the strongest movers with the reverse-grip curl, that brachialis becomes the stronger mover.

Remember, when we do the hammer curl we've got the brachialis, as well as the brachioradialis, and the long head. The long head's the stronger muscle so in the hammer curl it sort of takes over. With the overhand grip or reverse grip on the curl, the biceps are no longer strong movers—it's the brachialis that becomes the strongest mover along with the brachioradialis, which is weaker than the brachialis, so it becomes a great brachialis exercise.

Like I said, you want to include, at least occasionally—it doesn't have to be each workout that you train the biceps—but I would probably do it at least every other workout, at least, including a brachialis move like the reverse grip which is also going to hit the brachioradialis as well so you can kind of kill two birds with one stone, as well as using the hammer curls.

Let's talk about some program design now that we know what it takes as far as arm position to hit the specific areas of the biceps. When we're talking about program design, most people want to do a fairly even balance of exercises that work both the long head and the short head.

You want to include in a typical biceps workout, let's say your barbell curl, right? So, a typical biceps workout we're going to start with our main mass mover, our barbell curl. This is the exercise that's going to allow you to place the most overall—you're going to be able to use the most weight on barbell curls.

You want to do them at the beginning when you're freshest. Now, every rule is meant to be broken so you don't always want to do this—we could talk about pre-exhaust as another technique—but most cases you want to focus on doing your stronger moves while you're at your strongest because that's going to allow you to use the most weight. Using more weight's going to place more overload on the biceps, causing more damage, more fatigue—that's going to lead to better results.

I typically start with something like barbell curl, 3 sets of 8-10. Then, you can start getting into more long head or short head focus. Remember, the standard barbell curl—if you're going to use a regular, shoulder-width grip—is going to hit both long and short head fairly evenly. We move into incline dumbbell curl next, that's going to hit the long head. So let's see, we'll do 3 sets of 10-12. And then we do our high cable head to really hit that inner, short head, 3 sets, let's do 12-15. So we have a variety of rep ranges and a variety of exercises.

This is just one example of a fairly balanced biceps workout doing barbell curls to hit both heads—maximize your overload—then moving into the incline dumbbell curl to put a little more focus on the long head, and then finishing up with the high cable curl to focus on the short head.

Now, if this was a person who really wanted to bring up their long head, they're really trying to work on their peak? Then you could balance this—or sort of off-balance this, or unbalance it, however you want to say it—by doing more focus on long head exercises. When it gets to the barbell curl, he might want to start maybe Set 1 with a normal grip—so one set with the normal grip—and then maybe the last two sets he does with a very close grip, which is going to help hit more of that long head, right? Because we're medially rotating the arms in.

Then he's going to follow with incline dumbbell curl, another long head exercise, and then if he wants to keep it balanced I would also recommend doing the high cable curl, or maybe it's a preacher curl because, again, you don't only want to focus on one area. Even if it's your weak area, you still want to do exercises for the stronger area.

Here he's focusing on the long head, even at the start with the main barbell curl, continuing to focus on the long head with the incline, and then making up for the shorter head—to do some short head work. You could also talk about including a reverse-grip curl to hit more of that brachialis, maybe 2 sets here, 12-15, so that we're getting the brachialis. And then the opposite could be done for the short head.

If you want to work more on your biceps peak, it's fine, but you want to build some more thickness and hit that shorter, inner head? Then I would probably start, again, start with your barbell curl. But here, I would use the shoulder-width grip or wider, so one set shoulder width and then maybe two sets with a wide grip to hit more of that inner head.

Then, we would move into another short head exercise while the biceps are fresh, so maybe here we'll do high cable curl. Then we still want to hit some long head—like I said, don't neglect the long head, but we'll just move it down in the order—we're focusing on that weak area we want to bring up.

Moving the long head down on the priority list so it gets trained later in the workout when you're a little more fatigued, but since that's not your main goal—to bring up the long head, it's the short head—it's okay. So you move those exercises later into the workout, so let's say you do behind the back cable curl here for the long head. Then you can decide whether or not you want to round it out with some reverse-grip curls to hit more of that brachialis.

Those are just some examples of designing your program, but really—for those of you who know my program design philosophy, I'm all about variety. All about variety in exercise choices. I'm all about variety in rep ranges, and that goes for the biceps—you know, some people say, "Oh, you're doing three to five reps for incline dumbbell curl? Isn't that kind of heavy?" No. Any muscle—even abs, some of my ab workouts will be in the 3-5 rep range—these are muscles. How is the pec muscle any different from the biceps, any different from the abs?

Other than what they do, they're muscle tissue—they contract. They're designed the same way, the biceps and the abs, or rather the chest and the abs. So why would you go super heavy on chest—3-5 is okay—but when you get to curls or abs, you have to stay in the 12-15, maybe 10—no. Every muscle needs to be trained with a variety of weight and rep ranges, all the way down to the 2-5 range, all the way up to 30 reps and more—50 reps, I do 100 reps. Variety: It's absolutely critical to preventing stagnation. With the biceps, they're no different than any other muscle group.

Variety in weight, in rep ranges, in exercise selection—regardless of what your goal is, even if you're focusing on really bringing up your peak then you're going to swap around a lot of different exercises that are going to help to hit that long head of the biceps. Hammer curls, concentration curls, behind the back cable curls , behind the back band curls, incline dumbbell curls—mix it up. Exercise selection, exercise order, weight used, reps, rest periods, training frequency—that's the other critical factor when we're talking about program design.

There are two main ways a muscle grows, at least that we know right now. These are the theories—we really don't know how muscle grows because every time we discover something we realize that there's something else that's involved. Whenever we find something else that turns muscle protein synthesis on we realize that there's something that turns it off, because it's all checks and balances. So, we really know little on the control of muscle growth. However, we do know a few of the processes that are involved, and the first is muscle damage.

Muscle damage is the first way that the muscle grows. Basically, what happens is—if this was your biceps muscle, and that's the tendon attaching to the arm; this is all the striated muscle, this is the other tendon attaching at the top—if this is my long head, this would be composed of thousands and thousands—hundreds of thousands of muscle fibers. Tiny, microscopic, smaller than a hair—that's your muscle fiber, which is also a cell. So a muscle cell looks like this: A long, tiny hair.

If we put that under a microscope, what we notice when we increase the size of this is that we see a bunch of nuclei. If you look at an egg—crack open an egg—there's your white, there's your yolk. What is the yolk? That's your nucleus, right? The egg is a perfect example of a single cell. Almost every cell in the human body has one nucleus. One of the only cells in the body that has more than one nucleus is muscle.

When we damage a muscle—so let's say I did a real heavy set of curls, I did a bunch of eccentrics—it literally causes microtears in the muscle from that force. It's literally shearing the muscle apart and causing damage. So when you get this damage in an area you have other cells—immune cells, white blood cells—that come in here and they start removing all the debris. They get rid of all this broken-down material.

The other thing that happens is, once all that material's been removed, a new nucleus comes in—a brand new one. Now, the nucleus that was here wasn't destroyed, it's still there, just that this tissue is destroyed. So now, if this muscle fiber had four nuclei before, after this workout it's now got five. Do you know what happens in the nuclei? That's where all the muscle protein synthesis happens.

If you have a muscle fiber that has four nuclei and you increase it to eight nuclei, guess which one is making more muscle: The one with eight nuclei, because there are more areas that are building muscle within that muscle fiber. This is one of the main ways that muscle grows, these muscle fibers get damaged, the cells of the body remove the damage, and then they bring in a new nucleus so that this can all be rebuilt stronger than it was before. Now it's got an extra nucleus, which means there's another factory in that muscle fiber that's making muscle protein.

You know what happens? You never lose this nucleus. This is what "muscle memory" is, right here. This is the key to muscle memory . Why does a bodybuilder who stops training for ten years and then goes into the gym and in one month he almost regains his old shape, but a person who's never lifted could not transform their body in one month that way? Why? Because the trained lifter has more nuclei, so he's building muscle faster when he comes back. You never lose those nuclei. That's what muscle memory is. And that's one of the ways muscle grows.

Now, another way that muscle grows has nothing to do with damage, or you'd be sore every day. Who's sore every single day? Not many of us, but we can still grow without being sore. We talked about the nuclei, right? In the nuclei is where muscle protein synthesis happens, so another way to increase muscle growth is to increase the rate of muscle protein synthesis.

We could do that by—I showed you these nuclei, right?—we could do that by increasing the number of nuclei we have so that more of these are building, or we could actually increase the ability of each nucleus to produce protein. That is the main way that we grow without getting damage, by activating the genes in these muscle cells.

Your genes don't just determine your eye color and your height—that's your genotype; what we're talking about here is phenotype, and those are the changes that occur every day. Everything you eat, everything you do, everything you inhale turns on and off genes in your body. Some of them are in your muscle.

When you train, you're turning on genes—metabolic ones, and muscle-building ones—and that's one of the things I talk about with full-body exercise, why it's so effective. It's because it's keeping all these genes active and all these nuclei in these muscle cells, meaning you're burning calories. It also keeps the muscle-building activity of the genes that are involved in muscle protein synthesis ramped up, which is why frequency is important.

When we damage—remember, we damage, that's one way right? We cause damage in the muscle, then that has to be cleared out, all that garbage has to be cleared out. Then we bring in another nucleus. That's a slow process. That takes weeks, at least days for this to happen. When we're not causing damage, it's much faster—it's immediate. You workout and muscle protein synthesis goes up as long as you're providing enough protein. That's why you need protein post-workout, it's important. It goes up.

One way to increase muscle growth is to increase the number of these nuclei. Well, what did I say the other way was? To increase the activity of these nuclei. There are seven days in the week, right? Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, Saturday, Sunday.

If you trained arms only Monday, and activated those genes but didn't do it on Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, Saturday, Sunday, and waited until Monday again, that's seven days. But what if you hit it again on Tuesday and activated those genes again? And again on Wednesday, and activated them again—and Thursday, and activated them again, and Friday, turned them on—do you see why more frequent training can actually produce more muscle?

Two different ways: One is by damaging—make sure you read my Damage, Inc. article; the other is by frequently activating the gene activity. If you follow a program like my Six Weeks to Sick Arms , which is all about building bigger biceps—and literally, I don't think there's a human being, male or female, that hasn't gotten very close to at least an inch gain on their arms in six weeks. Almost everyone gains on this program, I haven't heard from anyone who hasn't gained anything on the Six Weeks to Sick Arms. It's that effective.

The reason it's effective is I use both of these techniques. We start off with muscle damage—get that damage, let the muscle heal—and then hit it frequently to get that gene activity up. So at the beginning of the program, we increased our nuclei by damaging, then mid-point into that program—now that you have more nuclei—we're going to increase the activity, how often we're going to activate them. That's why you're training three times a week with Six Weeks to Sick Arms. You're increasing the frequency. So it uses both of those techniques.

When you're designing your program you not only want to look at that one workout, "What exercises did I do in that one workout?" Well, how often am I training my biceps? Did I do negatives? If I did negatives, then I probably want to give my biceps some rest, allow this process to take place. Get the new nuclei, right? Then, once the recovery has happened, now let's keep hitting that new nucleus and all the other ones with exercise and protein to keep muscle protein synthesis going.

You need to be cognizant of not just that one workout, but what are you doing in that workout? Are you using negatives? Well, you probably want more rest time. If not, you've already done the negatives, you're doing more frequency of training then. You want to increase the frequency. So incorporate both of those techniques, but make sure you read my Six Weeks to Sick Arms because it really shows you precisely how to do that.

Now, let's talk about—real quick, I'm going to just talk about genetics real quick, the debate over—and I talked about this a bit on the peak, so—obviously, genetics are important, right? But genetics are only responsible for so much. Most people know my father. People have seen my dad, he does a lot of grip strength stuff. We're very similar body types. We both have great grip strength. His biceps suck compared to mine. Sorry, dad, that's just the fact. He doesn't train his biceps that often, he does more grip strength.

We have the same body type, but if you looked at my dad you'd say, "Well he doesn't have much peak." But we pretty much have the same biceps, so why do I have such a good peak, yet he doesn't, when genetics are such a factor? It's because of science. Like I said, your genetics will determine how much total peak you can have or whether or not you've got Robbie Robinson peak versus somebody else. No matter how bad your peak is, and no matter how lousy you claim your genetics are, you can make it better by following these techniques that I talked to you about changing arm position to focus more on that long head.

The other thing I'll say is about the length of your biceps. Now, people say, "Oh, well I read that—" Like I said, it's one long muscle fiber. Well, there's now evidence that we have some weaving of shorter fibers along with these longer ones, so that when you—and you can kind of see here on the short head here, at the end here when I flex it—where's that going?

It's not being pulled up all the way. It's contracting just—you can see these fibers pull in, they don't even contract length-wise, they actually contract more down because they're pulling, like I said, it's initiating—and what that does, like I said with the brachialis, if you have a shorter fiber here it initiates a better pull at the beginning.

When you look at things like data on abs, and there's a debate on lower abs versus upper abs, the abs are one muscle. Although you can see the delineation here, that's just different tissue. It's not—these aren't different muscle fibers. The muscle fiber of this ab is running down into this ab, down to this ab, all the way down—it's apparently one long fiber.

We also believe that there are some shorter fibers in the lower and upper abs, and in fact, when you look at data on leg raise exercises you can actually see more muscle activity in the lower portion of those muscle fibers. So can you actually work on the lower part of the biceps? Yeah, you could actually feel it too with preacher curls. The reason the preacher curls work is because—when I talked about the biomechanics here—right here, moving here? Well, if you're using free weights, this motion—like I said, it's angular—you're not providing much resistance right here, right? Because gravity is up and down.

Not until the arm is parallel to the ground is the resistance maximized. What you do is you bring your elbow forward. Now, when the arm is straight, I have maximal resistance, so it's maximizing the resistance at this part of the range of motion which, like I said, is helping to hit more of the muscle fiber in that area. Although you can't make your biceps much longer, you can build up a bit more of the lower head of the biceps by using that technique.

That's where I stand on genetics. As far as the novel tricks, I talked about a few already: Seated barbell curl, where you're going to sit and you're going to have a barbell on your lap, unlike a seated dumbbell curl. The dumbbells, you can go all the way down. We want to limit the range of motion here, because I'm weaker down here. If I'm focusing on this range of motion I'm staying in the strongest part, and I will hit fatigue when the biceps fatigue. I'll be able to use more weight because I'm not limited to that beginning portion of the range of motion.

The other thing I'll add is on bands, and I showed you a few band exercises. Now, what people don't realize with bands is the bands aren't a, "Oh, it's a Plan B when I don't have free weight. It makes a good replacement." No, bands provide what's known as "linear variable resistance", which simply means they get harder the further you stretch them.

When I'm doing band curls the band provides less resistance in this position, more resistance in this position, because the further I stretch it the harder it is to continue stretching. What does that mean for the curl? Well, remember I talked about the strength curve. You're weakest here, right? Guess what—the band is providing the least tension here, when you're the weakest.

As the bands get harder, guess what—that's when you get stronger. So bands work well with the strength curve for curls in particular, and the nice thing here is because the tension continues to build all the way through the range of motion, at the top of the range of motion of the curl when I'm using a barbell now the bar is falling toward me so I'm not really resisting. To get a peak contraction with a free weight at the top of the curl is almost impossible. With bands, guess what—it's a true peak contraction, because you're still resisting even in that top position.

It helps, like I said, with the strength muscle curve of the curl and the muscle involvement in getting that peak contraction. Just one tip for your biceps training, like I said, that most people really don't think about.

Seated, the main points are, remember: Changing your arm position to hit the long, the short, the brachialis, brachioradialis; remember to train with both heavy weight negatives to cause some damage, then give it enough rest; and then change up your frequency, training the biceps more frequently—at least 2-3 times a week, if not even daily.

I'll leave it now to questions, but I'll post this—well, I'm going to post this on my Facebook, right? I'll save this on my Facebook, so for those of you who have questions that don't get answered—obviously, like I said, I'm going to choose five now—but if you still have questions, you can post them any time at this video. This video will be saved on my Facebook page. Post your question, and I will get you an answer within the next 24 hours. This is the best place to go.

Question: "I’m on your 12-week Shortcut to Size program. What do you recommend I do because I can't eat 7-9 times a day? My body physically can’t eat that much"

It's a great question. Nutrition is critical for building bigger arms. As a matter of fact, we say it takes about 10 lbs to gain an inch on your arms. To put an inch on your arms, you need to gain almost about 10 lbs of body weight, seems to be pretty equivalent. When you've gained 10 lbs, you'll have an extra inch or so. Not always, because obviously you could get leaner at the same time, but nutrition is critical.

So, the question is, on my Shortcut to Size you're eating fairly frequently and you're eating all day. This isn't intermittent fasting . Remember, I intermittent fast, but again I'm trying to stay super—I never get above 5% body fat, I never allow myself to go above that. So I'm always staying super-lean. To stay super-lean, intermittent fasting is the easiest way to do that.

If you're trying to maximize muscle growth following my Shortcut to Size plan , I don't recommend intermittent fasting. You certainly could do it, but you're not going to maximize your size. With Shortcut to Size, you're eating a lot, and you're eating frequently, but again—Shortcut to Size. Your goal is to build as much as muscle as you can.

If you find you can't fit in—if it's just meal frequency, you're just not able to eat that many meals, then what you can do is combine meals. And what I mean by "meals", I'm not talking about combining lunch and dinner, I'm talking about the snacks that you're having in between those meals. You can combine those into the same meal if it's just the frequency.

If it's down to just calories, you just can't consume enough? I would either recommend using my mass gainer or watching my how to build your own mass gainer video so that you're drinking more of those calories, because you definitely want to be getting ample amounts of protein, as well as carbs and especially fat. So make sure you're hitting those macros to truly maximize your results on Shortcut to Size.

Question: "Do you recommend training biceps and triceps on the same day?"

Good question. So, should you train your biceps and triceps on the same day? Yes—and no. Variety, right? It's even in the way that you mix up your training. I mainly do full-body training now, but again my goal is to be super-lean as well as muscular, perform well, be strong. Due to my goal—and health-wise, too, I just think overall health is better—I'm 50, so that's one of my main concerns, maintaining my health—I go for full-body training. With full-body training, I'm doing biceps and triceps together every single day.

I also like supersetting biceps and triceps. They work well together because it's opposing muscle groups. They work as a great superset. That doesn't mean you should always train them together, and in fact, some people claim you're better off separating them. The sort of "broscience" says, "Well, if you're getting blood flow to the biceps, and you're training triceps, and you're maximizing pump, it's hard to get blood flow to two muscles going at the same time. Maybe there's not enough, you should focus on one."

I find that hard to believe, whether that would really matter. You can do them both. But just variety alone, mixing it up—if your body is used to always training triceps with biceps, then it's a good idea to switch it up and not train triceps with biceps, or if you're used to always training them separate—you do triceps and chest, back and biceps, and those are on separate days—then it's time to do them together.

Remember, the best workout is the one you're not doing—and no, I don't mean you should stop doing the one you're currently on to do something else, but when you've completed one program it's time to move on, mix it up, and use a different variety. With arm training, a good way to mix it up is like with that question: Train them together some periods, train them separately other periods.

Question: "Due to my right arm dominance, it's larger. Do you recommend to go heavier on the weak arm to equalize the size?"

A common question I get—so common that I made a video and a program called Biceps Imbalance Training . He asks should you just go heavier on the weaker arm? Well, that's an oxymoron. How can you go heavier on the weaker arm? It's the weaker arm. If it's weaker than the other arm, how are you going to train it heavier than the other arm unless you're undertraining the other arm?

That's typically what ends up happening, most people end up undertraining the one that is better-developed so that the other one catches up. What happens is it catches up because the other one gets smaller while the other one gets bigger, which is not really what you want to do. You want to keep the size of that dominant arm and bring up the other one.

How do you do that, it's weaker? Frequency. It all comes down to training frequency. Go to either my YouTube channel and look up my Biceps Imbalance training, or go to JimStoppani.com. You can get it there as well, the actual program, so that you can follow it. I cover it pretty well. That's an old video, so if you haven't seen me with hair you're going to see quite a hairdo, but a great technique.

It's really about training that weaker arm more frequently, and you'll see how I work it in. I have you doing more work on arm day, and then you include just that one arm on other days during the weak where you're not training the other arm. It comes down to the frequency.

A lot of experts say, "Well, train heavier," but it's the weaker arm. How do you train the weaker arm heavier unless you undertrain the other arm? That's really what that comes down to. The answer really is that it's about frequency.

I put that out probably a decade ago, and literally thousands of people have gotten amazing results. I will say, you take that same concept—you'll figure it out—and you can apply it to any other muscle group that you have an imbalance on.

Question: "Do you have any advice to deal with elbow tendonitis?"

So, with elbow tendonitis, I don't know when that's occurring for you but I will say, even though we're talking about biceps today, I'm going to start with triceps. If you get elbow tendonitis doing triceps exercises—so you'll notice it probably on overheads, lying extensions when the arm is stretched, even pressdowns maybe to some degree—if you're getting a lot of elbow pain during triceps moves what you want to do is start moving away—not permanently, just temporarily while you're recovering—moving away from single-joint exercises that put a lot of stress on that tendon.

What you want to start doing is moving towards more multi-joint movements—dips, close-grip bench press—so that you have both shoulders and chest helping the triceps move that weight, so it's not taking all the load and irritating it. Move into more multi-joint exercises.

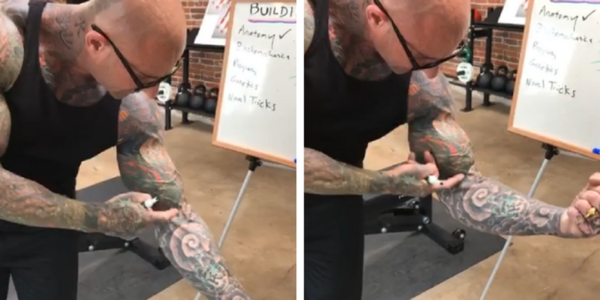

If you're getting it on biceps, it's going to differ whether you are feeling it more on the inner part of the arm or the outer part of the arm. Both tendonitis, just different main muscles. One's more your extensors—that's over here—and one's more your flexors, that's on the inside. Both, however, will do very well with Hand X Bands. With the Hand X Band—I carry this around all the time, I use it for pre-hab.

The way I came across Hand X Band—and for those of you who don't know, you hear me talk a lot about Hand X Band. I'm not affiliated with them whatsoever. I make no money off of Hand X Band, they've actually—they're from Connecticut, so a high school buddy of mine is good friends with one of the owners, and they connected me and it was at a time when I had horrible tendonitis. I started using the Hand X Bands, cured my tendonitis, and ever since I've been pretty much pain-free as long as I keep using it for pre-hab.

They come in different resistance, so the orange one is called "the Trainer". This is the lightest one, and this is the one you want to get because you don't want to have much resistance. You just want to be able to extend your fingers with a little bit of resistance but not too much that it irritates your tendonitis. You get it on the fingers and now what this does is it allows you to use the extensor muscles that open the hand.

The problem is when you're doing curls you're gripping, right? One of the things I wanted to talk about with the novel tricks was using an open grip when I do—when you see me do curls, I use an open grip, meaning the thumb is underneath because I don't want to grab the dumbbell or the barbell. We grab, we squeeze, and then what happens is we work the muscles that close the hand—those become strong—the muscles that open the hand don't get any work, no resistance this way—we're always squeezing, right? So the muscles become unbalanced and then it leads you to getting injuries.

You don't want to be squeezing, so first thing is to make sure you're using an open grip when you do curls, and this will help to focus more on the biceps—less on the forearms, as well. The Hand X Band—because, like I said, we're doing all that squeezing—this is the opposite movement, and for those of you who have gone through my Super-Man program where I introduced you to things like straight-arm pushdowns and toe raises to work the opposing muscles—the muscles on the front of the shin to balance out the calf muscles, the lower traps to balance out the upper traps—this is the same thing.

We're gripping all the time, but we never are having resistance this way. The Hand X Band is one of the best things I've found that helps. You could use the regular elastic band ones, but they don't stay on the fingers when you open it up. What I like about the Hand X Band is it has the little finger slots so you can keep the resistance where you want it and you can change your resistance by shortening or lengthening the lever arm. Works amazingly well.

What you want to do with this is you want to do different positions. You want to do it with a supinated, you want to do it with a pronated, overhand, bent, all different directions. You'll feel it working the different muscles based on how you move your hand, and remember it goes with my philosophy in training: Those small little changes make a big difference in the muscle. Definitely get a Hand X Band to start working those forearm muscles, and continue using that periodically. I try to do it at least three times a week as pre-hab to prevent any more tendonitis.

Question: "What about using band resistance in conjunction with free weight? I see a lot of guys using dumbbells with bands. It seems redundant. Is there any benefit to this?"

It's not redundant at all. Basically, what they're doing is—the way that athletes use bands. We don't think of curls as really an athlete exercise, but if you did the bench press—with the bench press, we could do—run this under the bench, and this is—we're using my JYM Strength Bands . What I really love about these is it makes it so easy to do exactly what the question is: Combine free weights with bands.

The majority of research that's done in athletes and bands is used this way, where they use both free weights and bands. So they'll take a bench press or squat and combine free weights with the band resistance. Then what you're getting is the free weight resistance, right? But in addition, you're getting the linear variable resistance.

Now you have a consistent weight on the dead weight, right? Our free weight is consistent, so when he lowers it the band resistance decreases. He's getting both resistance from the bands and the free weights. Remember, the band resistance changes, right? The shorter the bands, the less resistance; the longer, the more. The free weight, the dead weight on the bar, is going to stay the same.

He's got 135 lbs on the bar, which is going to be always 135 lbs, always going to provide at least 135 lbs on the negative. The bands he's using are 23 lbs, so in addition, he has about 23 lbs at least in the top position. When he goes down it's going to be considerably less. If he were just using bands, there would be no consistent weight going down, but here he as at least the 135 lbs dead weight going down as the bands—so it's a way to combine both that linear variable resistance with the free weight.

What they find is that athletes who train this way get more muscle than athletes who use just free weights without the bands. It's not redundant at all, and it can work great—I'm showing you here with a barbell, and if you want to do a dumbbell set-up, there are a couple ways you could do it.

Because you have to hold on—so if I have the handle here it makes it difficult for me. I still could sort of get this curl done this way, but it's a little wonky, right? So now I've got—just like on the bench press—I've got the 20 lbs of dead weight that's always there, but then, in addition, I have this 13 lbs that maximize in this position, but decrease in this position.

One of the easiest ways to do it, which is again why I love this system that I have here, is you could do this wearing it as a wristband, so now you've got the resistance here on your wrist and then you can hold on to the dumbbell. So now I've got dumbbell dead weight along with the linear variable resistance from the bands giving me the best of both worlds. Like I said, the research shows that it's far superior to just using free weight. Variety of not just exercises but also the tools that we're using, different types of resistance.

Congrats, everyone who won a JYM System. Again, that's going to be a Pre JYM, a Post JYM—that's both the Active Matrix and the Fast-Digesting Dextrose—and Pro JYM. Everything you need around workouts. You tell me what flavors you want, the five of you, and I'll get those right out to you.

I hope everyone enjoyed today's tutorial. Expect more of these. Hit me up with what you want to see. Obviously, we'll do triceps, we'll do chest. We'll focus on different exercises, maybe I'll do a bench press one, a deadlift one. We'll mix it up, there's a lot to cover. I really love the live sessions because I like just sort of talking off the cuff without having any real plan other than to get you guys great advice on how to train, and eat, and live.

Building bigger biceps, I hope you guys enjoyed it. Put it all to good use. If you have any more questions, go right to this video—I'll save this on my Facebook page —post your question, and I promise I will get you guys an answer. As always guys, stay JYM Army Strong.

Related Articles